Yurts to Universities

Yurts to Universities is a private non-profit foundation dedicated to assisting Turkmen girls and women go to school. Many are children of Afghan refugees who live in Pakistan, they have very few rights and are are exposed to arrest and deportation. Girls remaining in Afghanistan are not able to attend school beyond the sixth grade. Founder Terry Reid has been helping Afghan refugees since the 1980's when, on a buying trip to Afghanistan, he was caught up in the maelstrom of the Soviet invasion.

Meet Dr. Haleema

Dr. Haleema started off weaving rugs like many Turkmen women that came before her. But unlike most of the Turkmen woman, she has gone to university and earned a degree. She is the second Turkmen woman to earn a degree through grants provided by Yurts to Universities. Dr. Haleema now has a doctorate in medicine and is in her residency at a hospital in Pakistan.

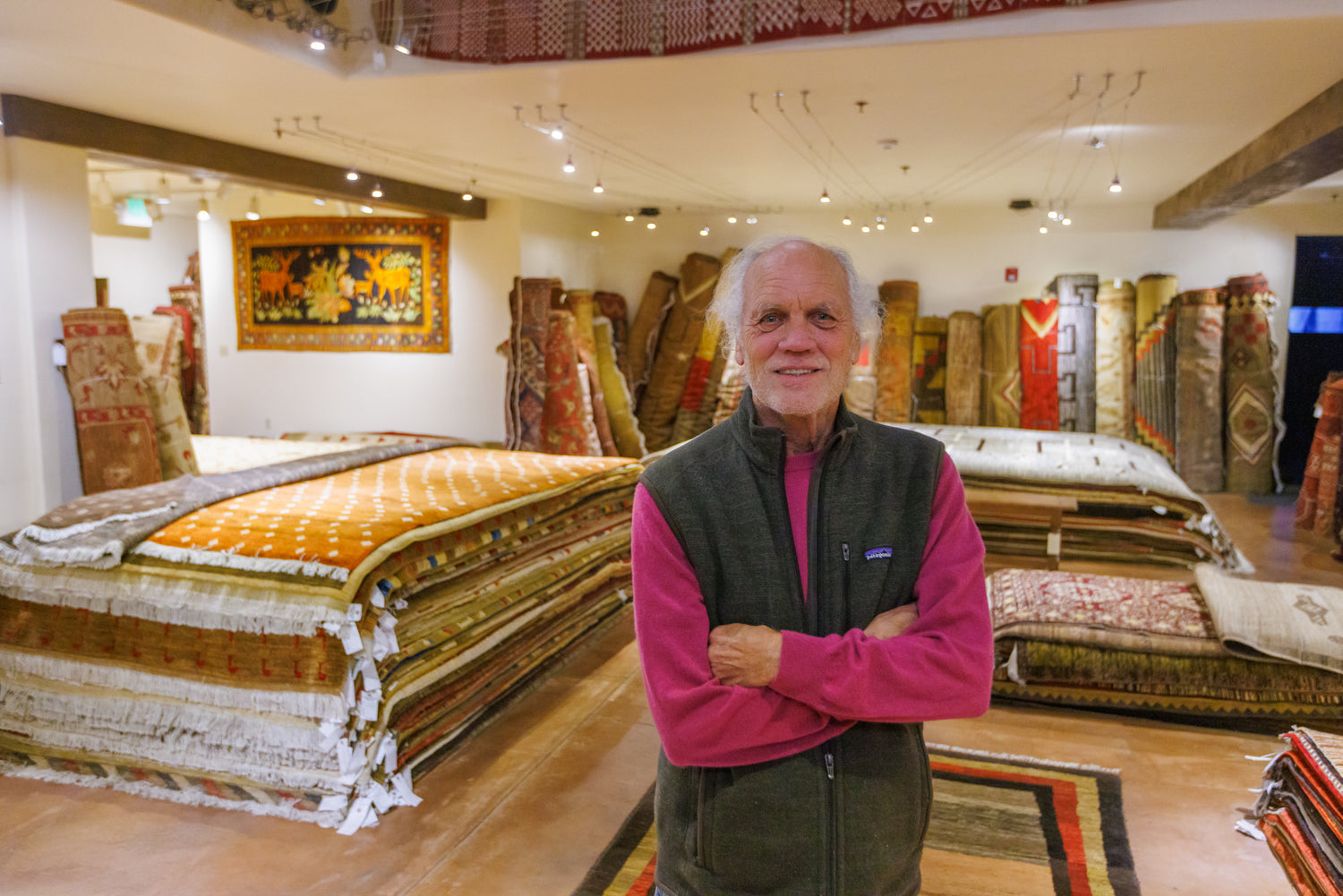

Terry's Story

Terry witnessed his Afghan friends’ lives destroyed. Some did not survive. Millions of Afghans gathered their children and a few belongings and fled to refugee camps in Pakistan.

Displaced with few rights and living in the squalor of the camps, Afghans turned to their mothers and wives who possessed ancestral knowledge of carpet weaving. Hand-knotted carpets made on home looms have historically been highly valued, not only in the home but also for trade.

Collapsible content

Read More

I had made many friends in the camps and especially liked working with the Turkmen people as I found them outgoing, industrious and intelligent. But the rugs they made with inferior materials, while beautiful, were limited in design and color. I wanted to see them weave rugs like the antique rugs that I had been collecting and selling over the years; carpets that became even more luxurious with age.

I asked my friend Kamil to procure high mountain, hand-spun wools from Moldari nomad herders. Wool grown at high altitudes produces the strongest and most lanolin-rich fibers. I also asked them to relearn natural dying. Hearing this request, Kamil said “I will go to the old woman” as she was one of the last to know natural dyes, like pomegranate rinds, walnut husks and madder root, which over the decades had been replaced with synthetics. Naturally dyed carpets, with normal care, remain vibrant for decades. Carpets using more modern materials, like most handmade rugs available commercially, do not age well.

I am inspired by Fatima* and her younger sister who grew up in a refugee camp. Fatima* is now getting her master’s degree in computer science and Aliye* is in her last year of medical school. These young women are certainly among the first in Pakistan’s refugee community to seek advanced degrees. There are hundreds of other Afghan children from many different tribes who were educated at Project schools and they are now doctors, engineers, journalists, teachers and other professions.

Hamid Shojayee is another successful young person who started life in a refugee camp. Over the years, I encouraged and supported his education. After studying computer science at a Pakistan college, Hamid found there was no work for his skills there. In 2009, he went back to Afghanistan to work as a combat translator for the U.S. Army. After five years and because his life was in danger, he was granted a visa to this country. He landed in Fort Worth, Texas because he knew another Afghan there. Today, Hamid has his own trucking business with seven trucks and many employees.

After my partner in life and business, Sharon Davies, recently passed, I decided to start a charitable organization so that our efforts might continue for many years. I want to help to educate Turkmen women and girls by awarding grants to deserving applicants. Currently, no non-profit groups serve the Turkmen people, specifically. I believe, as my wife Sharon did, that educating girls and women is a key to progress for the entire culture.

*We use aliases for these young women to protect them from forces in Pakistan and Afghanistan who oppose education for girls.